Key Takeaways

- AI-generated images are harder to spot

- AI detection tools exist, but are underused

- Artists’ participation is crucial in preventing misuse

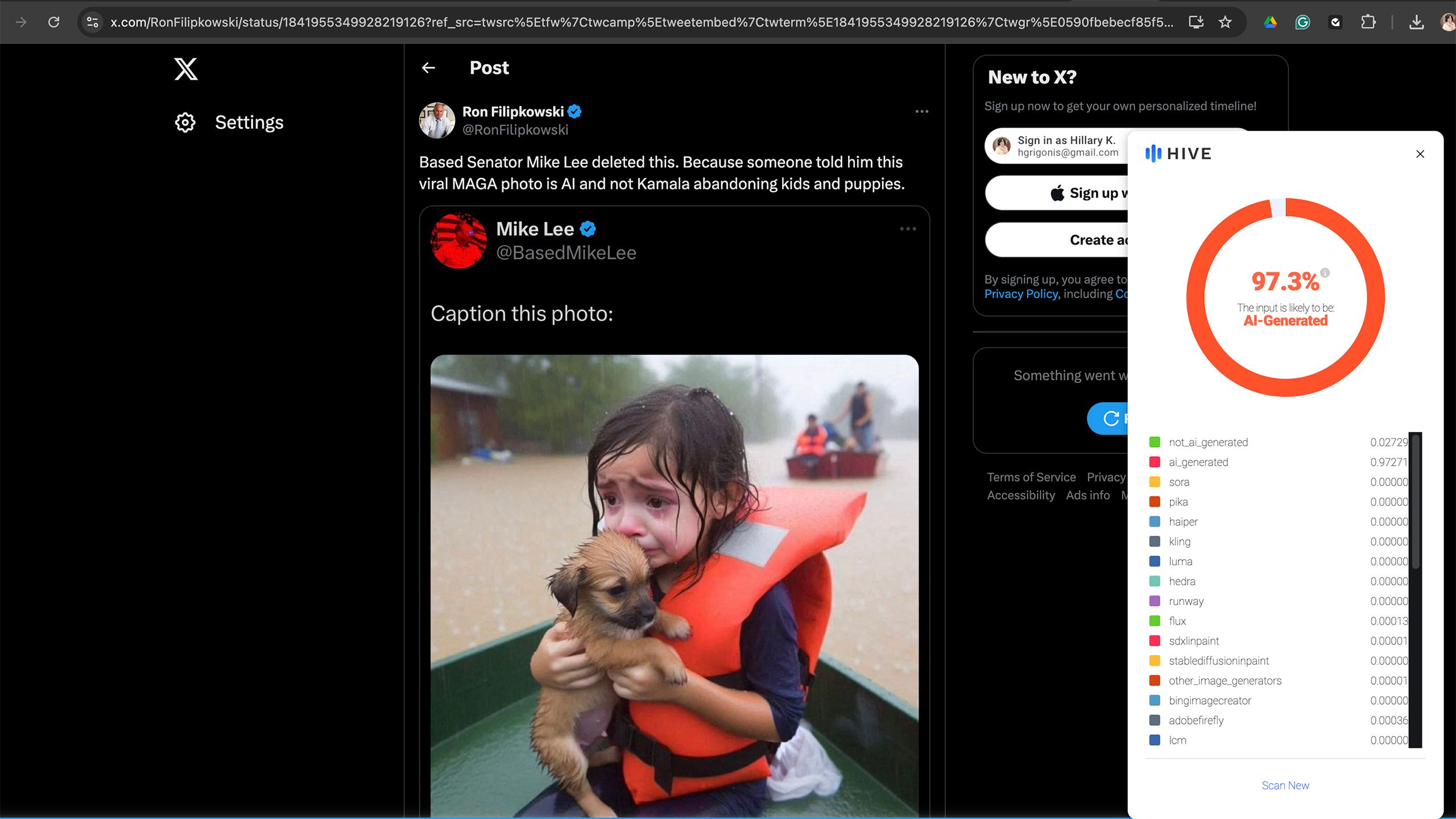

In the wake of the devastation caused by Hurricane Helene, an image depicting a little girl crying while clinging to a puppy on a boat in a flooded street went viral as a depiction of the storm’s devastation. The problem? The girl (and her puppy) do not actually exist. The image is one of many AI-generated depictionsflooding social media in the aftermath of the storms. The image brings up a key issue in the age of AI: is growing faster than the technology used to flag and label such images.

Several politicians shared the non-existent girl and her puppy on social media in criticism of the current administration and yet, that misappropriated use of AI is one of the more innocuous examples. After all, as the deadliest hurricane in the U.S. since 2017, Helene’s destruction has been photographed by many actual photojournalists, from striking images of families fleeing in floodwaters to a tipped American flag underwater.

But, AI images intended to create misinformation are readily becoming an issue. A study published earlier this year by Google, Duke University, and multiple fact-checking organizations found that AI didn’t account for many fake news photos until 2023 but now take up a “sizable fraction of all misinformation-associated images.” From the pope wearing a puffer jacket to an imaginary girl fleeing a hurricane, AI is an increasingly easy way to create false images and video to aid in perpetuating misinformation.

Using technology to fight technology is key to recognizing and ultimately preventing artificial imagery from attaining viral status. The issue is that the technological safeguards are growing at a much slower pace than AI itself. Facebook, for example, labels AI content built using Meta AI as well as when it detects content generated from outside platforms. But, the tiny label is far from foolproof and doesn’t work on all types of AI-generated content. The Content Authenticity Initiative, an organization that includes many leaders in the industry including Adobe, is developing promising tech that would leave the creator’s information intact even in a screenshot. However, the Initiative was organized in 2019 and many of the tools are still in beta and require the creator to participate.

The image brings up a key issue in the age of AI:

Generative AI

is growing faster than the technology used to flag and label such images.

Some Apple Intelligence features may not arrive until March 2025

The first Apple Intelligence features are coming but some of the best ones could still be months away.

AI-generated images are becoming harder to recognize as such

The better generative AI becomes, the harder it is to spot a fake

I first spotted the hurricane girl in my Facebook news feed, and while Meta is putting in a greater effort to label AI than X, which allows users to generate images of recognizable political figures, the image didn’t come with a warning label. X later noted the photo as AI in a community comment. Still, I knew right away that the image was likely AI generated, as real people have pores, where AI images still tend to struggle with things like texture.

AI technology is quickly recognizing and compensating for its own shortcomings, however. When I tried X’s Grok 2, I was startled at not just the ability to generate recognizable people, but that, in many cases, these “people” were so detailed that some even had pores and skin texture. As generative AI advances, these artificial graphics will only become harder to recognize.

Political deepfakes and 5 other shocking images X’s Grok AI shouldn’t be able to make

The former Twitter’s new AI tool is being criticized for lax restrictions.

Many social media users don’t take the time to vet the source before hitting that share button

While AI detection tools are arguably growing at a much slower rate, such tools do exist. For example, the Hive AI detector, a plugin that I have installed on Chrome on my laptop, recognized the hurricane girl as 97.3 percent likely to be AI-generated. The trouble is that these tools take time and effort to use. A majority of social media browsing is done on smartphones rather than laptops and desktops, and, even if I decided to use a mobile browser rather than the Facebook app, Chrome doesn’t allow such plugins on its mobile variant.

For AI detection tools to make the most significant impact, they need to be both embedded into the tools consumers already use and have widespread participation from the apps and platforms used most. If AI detection takes little to no effort, then I believe we could see more widespread use. Facebook is making an attempt with its AI label — though I do think it needs to be much more noticeable and better at detecting all types of AI-generated content.

The widespread participation will likely be the trickiest to achieve. X, for example, has prided itself on creating the Grok AI with a loose moral code. The platform that’s very likely attracting a large percentage of users to its paid subscription for lax ethical guidelines such as the ability to generate images of politicians and celebrities has very little monetary incentive to join forces with those fighting against the misuse of AI. Even AI platforms with restrictions in place aren’t foolproof, as a study from the Center for Countering Digital Hate was successful in bypassing these restrictions to create election-related images 41 percent of the time using Midjourney, ChatGPT Plus, Stability.ai DreamStudio and Microsoft Image Creator.

If the AI companies themselves worked to properly label AI, then those safeguards could launch at a much faster rate. This applies to not just image generation, but text as well, as ChatGPT is working on a watermark as a way to aid educators in recognizing students that took AI shortcuts.

Adobe’s new AI tools will make your next creative project a breeze

At Adobe Max, the company announced several new generative AI tools for Photoshop and Premiere Pro.

Artist participation is also key

Proper attribution and AI-scraping prevention could help incentivize artists to participate

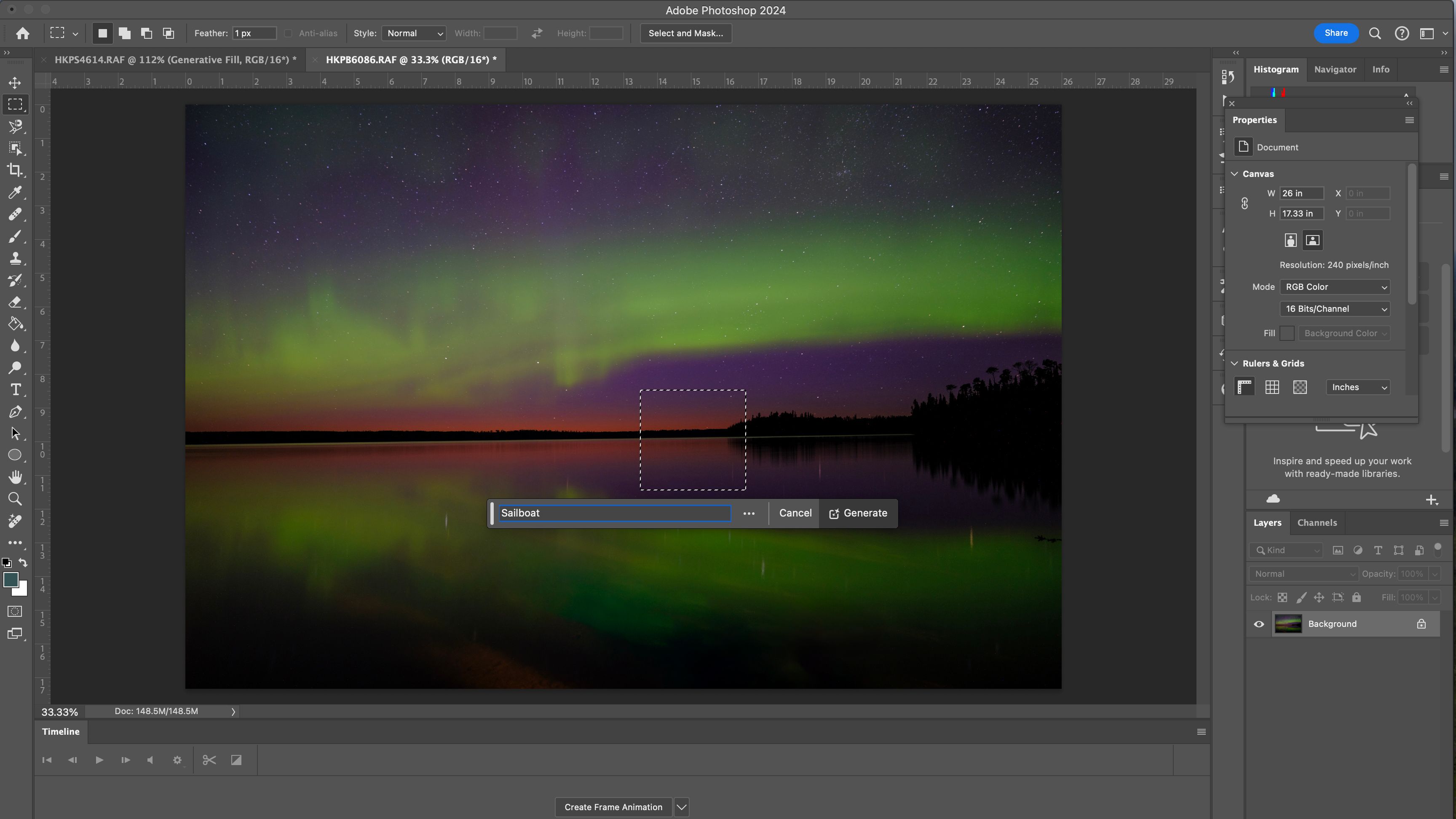

While the adoption of safeguards by AI companies and social media platforms is critical, the other piece of the equation is participation by the artists themselves. The Content Authenticity Initiative is working to create a watermark that not only keeps the artist’s name and proper credit intact, but also details if AI was used in the creation. Adobe’s Content Credentials is an advanced, invisible watermark that labels who created an image and whether or not AI or Photoshop was used in its creation. The data then can be read by the Content Credentials Chrome extension, with a web app expected to launch next year. These Content Credentials work even when someone takes a screenshot of the image, while Adobe is also working on using this tool to prevent an artist’s work from being used to train AI.

Adobe says

that it only uses licensed content from Adobe Stock and the public domain to train Firefly, but is building a tool to block other AI companies from using the image as training.

The trouble is twofold. First, while the Content Authenticity Initiative was organized in 2019, Content Credentials (the name for that digital watermark) is still in beta. As a photographer, I now have the ability to label my work with Content Credentials in Photoshop, yet the tool is still in beta and the web tool to read such data isn’t expected to roll out until 2025. Photoshop has tested a number of generative AI tools and launched them into the fully-fledged version since, but Content Credentials seem to be a slower rollout.

Second, content credentials won’t work if the artist doesn’t participate. Currently, content credentials are optional and artists can choose whether or not to add this data. The tool’s ability to help prevent scarping the image to be trained as AI and the ability to keep the artist’s name attached to the image are good incentives, but the tool doesn’t yet seem to be widely used. If the artist doesn’t use content credentials, then the detection tool will simply show “no content credentials found.” That doesn’t mean that the image in question is AI, it simply means that the artist did not choose to participate in the labeling feature. For example, I get the same “no credentials” message when viewing the Hurricane Helene photographs taken by Associated Press photographers as I do when viewing the viral AI-generated hurricane girl and her equally generated puppy.

While I do believe that the rollout of content credentials is a snail’s pace compared to the rapid deployment of AI, I still believe that it could be key to a future where generated images are properly labeled and easily recognized.

The safeguards to prevent the misuse of generative AI are starting to trickle out and show promise. But these systems will need to be developed at a much wider pace, adopted by a wider range of artists and technology companies, and developed in a way that makes them easy for anyone to use in order to make the biggest impact in the AI era.

I asked Spotify AI to give me a Halloween party playlist. Here’s how it went

Spotify AI cooked up a creepy Halloween playlist for me.

Trending Products

Cooler Master MasterBox Q300L Micro-ATX Tower with Magnetic Design Dust Filter, Transparent Acrylic Side Panel…

ASUS TUF Gaming GT301 ZAKU II Edition ATX mid-Tower Compact case with Tempered Glass Side Panel, Honeycomb Front Panel…

ASUS TUF Gaming GT501 Mid-Tower Computer Case for up to EATX Motherboards with USB 3.0 Front Panel Cases GT501/GRY/WITH…

be quiet! Pure Base 500DX Black, Mid Tower ATX case, ARGB, 3 pre-installed Pure Wings 2, BGW37, tempered glass window

ASUS ROG Strix Helios GX601 White Edition RGB Mid-Tower Computer Case for ATX/EATX Motherboards with tempered glass…